Moloch Traps: The Physics of Coordination Failure and the Protocol Exit

Civilizational progress is constrained by a recurring structural failure in collective action. This paper formalizes Moloch traps as a class of multipolar coordination failures and advances the thesis that durable escape requires a transition from political to protocol-based coordination.

Moloch Traps: The Physics of Coordination Failure and the Protocol Exit

Abstract

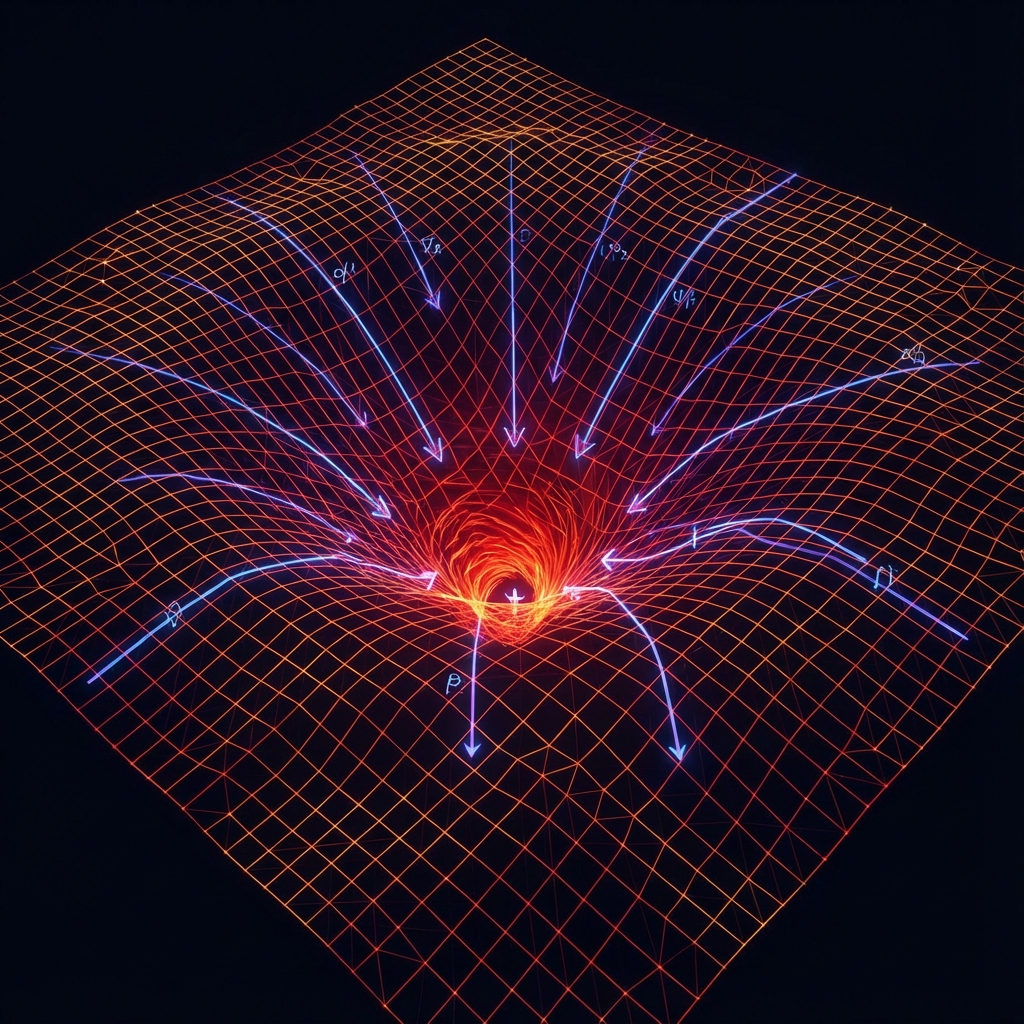

Civilizational progress is constrained not by a scarcity of resources or intelligence, but by a recurring structural failure in collective action. This pathology manifests when rational agents, strictly maximizing their individual utility functions, collectively produce an outcome that is Pareto-inefficient for the group. In contemporary discourse, this dynamic has been personified as "Moloch," a symbolic representation of systemic incentive gradients that reward defection over cooperation. This paper formalizes Moloch traps as a class of multipolar coordination failures governed by game-theoretic constraints, examines the entropic degradation of traditional institutional countermeasures, and advances the thesis that durable escape requires a phase transition from political coordination to protocol-based coordination. Such a transition moves governance from discretionary human enforcement to immutable, mathematical constraint systems—reshaping payoff matrices at the infrastructure layer rather than attempting behavioral reform at the application layer.

1. The Definitions of Defeat

1.1 Moloch as a Formal Failure Mode

In Meditations on Moloch, Scott Alexander describes a systemic pathology in which every actor within a system desires a better outcome, yet structural incentives compel behavior that produces a worse one [1]. This failure mode differs from ignorance, incompetence, or malice. Each participant understands the negative outcome and actively wishes to avoid it. The system nonetheless converges toward that outcome through individually rational decisions.

This class of failure is best described as a multipolar trap, a term popularized by Eliezer Yudkowsky to describe situations where many agents, none of whom control the system, collectively generate catastrophic equilibria through competitive pressure [2]. Multipolar traps arise when cooperation produces diffuse, delayed, or uncertain benefits, while defection produces immediate, localized, and reliable gains.

The defining characteristic of a Moloch trap is inevitability under existing incentives. Moral exhortation, education, or goodwill exert negligible influence once the payoff gradients dominate behavior.

1.2 The Two-Income Trap

Elizabeth Warren and Amelia Warren Tyagi documented a canonical modern Moloch trap in The Two-Income Trap [3]. During the mid-twentieth century, a single household income could reliably support housing, education, healthcare, and savings. As labor force participation expanded, particularly among women, household income increased. Rather than producing long-term security, the added income was absorbed by positional goods, particularly housing in districts associated with strong public schools.

The competitive bidding process altered the equilibrium. Families that retained a single-income model experienced immediate loss of access to desirable neighborhoods and schools. Families that adopted two-income structures maintained relative position but surrendered time, flexibility, and resilience. The system stabilized at a higher workload equilibrium without improving aggregate welfare.

This outcome satisfies all criteria of a Moloch trap. Each family prefers a world where one income suffices. No family can unilaterally return to that world without incurring severe penalties. The system enforces conformity through market mechanisms rather than explicit coercion.

1.3 The Arms Race

The arms race represents the archetypal coordination failure studied in game theory and international relations. In a simplified two-player model, two nations each prefer a world where neither invests heavily in weapons, freeing resources for domestic development. Each nation also understands that unilateral disarmament creates existential vulnerability.

The Nash equilibrium therefore favors mutual armament, despite mutual preference for disarmament [4]. The resulting equilibrium maximizes cost, risk, and instability while minimizing welfare. The rational strategy for each agent produces an irrational outcome for the system.

This dynamic extends beyond military contexts. Advertising escalation, financial leverage cycles, academic credential inflation, and algorithmic content optimization all follow similar incentive gradients [5].

1.4 The Axiom of Moloch

The recurring structure across these examples suggests a governing principle:

In any unconstrained system where the marginal return on defection exceeds the marginal return on cooperation, the system will converge toward a Nash equilibrium of maximal defection.

This axiom reflects the deterministic nature of incentive fields. Values, intentions, and cultural norms exert influence only as second-order variables; they cannot sustain cooperative equilibria against a dominant first-order incentive gradient.

2. Institutional Decay

2.1 The Leviathan as a Historical Countermeasure

Historically, societies constructed large-scale institutions to suppress Molochian dynamics. Thomas Hobbes framed the state as a Leviathan that imposes order by altering incentives through centralized authority [6]. Religions encoded moral constraints and collective rituals that rewarded cooperation and punished defection [7]. Guilds enforced quality standards and limited destructive competition within trades [8].

These institutions functioned by reshaping payoff matrices through enforcement, legitimacy, and shared belief. Defection carried consequences severe enough to outweigh short-term gains.

2.2 The Agency Problem

As institutions scale, they encounter the principal-agent problem formalized by Jensen and Meckling [9]. Decision-makers within an institution pursue incentives aligned with personal advancement rather than institutional purpose. Over time, institutional survival and expansion become dominant goals.

In bureaucratic systems, a solved problem reduces budget, authority, and relevance. An unsolved problem sustains funding, staffing, and political justification. Rational agents within the institution therefore optimize for problem management rather than problem resolution.

This dynamic appears consistently across regulatory bodies, healthcare systems, educational administrations, and international organizations [10]. The institution becomes another agent subject to Molochian pressures rather than a counterforce.

2.3 Complexity as Entropy

Joseph Tainter’s analysis of societal collapse identifies complexity as an entropic function of problem-solving [11]. Institutions respond to stress by adding layers of regulation, oversight, and procedure. Philosophically, this is an attempt to reduce volatility; functionally, it increases fragility.

In thermodynamics, closed systems tend toward maximum entropy. Bureaucracies function similarly: without external energy (reform/competition), they drift toward maximum administrative density. In US healthcare, administrative overhead exceeds 30% of expenditure [12]. In higher education, administrative staffing growth isolates the institution from its core purpose [13].

Complexity preserves institutional continuity in the short term by dampening variance, but it guarantees long-term sclerosis. The system becomes too rigid to adapt, yet too heavy to move.

3. The Protocol Exit

3.1 The Limits of Human Governance

Given that human-administered institutions inherit the same incentive vulnerabilities they aim to suppress, improvement through leadership reform or ethical training yields diminishing returns. The failure resides in the structure rather than the character of participants.

A durable solution requires altering the physics of coordination rather than optimizing behavior within flawed incentive fields.

3.2 Coordination at the Infrastructure Layer

Protocols represent a distinct category of governance. A protocol defines allowed state transitions through formal rules enforced by computation rather than discretion. In such systems, violations fail to execute rather than triggering punishment.

Bitcoin introduced this model to monetary coordination by enforcing scarcity, transaction validity, and settlement finality through cryptographic consensus rather than central authority [14]. Ethereum extended the model to generalized state transitions via smart contracts [15].

By embedding rules into the infrastructure layer, protocols eliminate entire classes of defection. Double spending, unauthorized issuance, and unilateral rule changes become computationally infeasible rather than socially discouraged.

3.3 Immutable Constraint Systems

In protocol-based systems, incentives are constrained by design. The payoff matrix excludes forbidden moves. This transforms coordination from a behavioral problem into a mathematical one.

Game theory research demonstrates that restricting strategy spaces can stabilize cooperative equilibria that remain unreachable under unconstrained conditions [16]. Protocols implement such restrictions universally and continuously.

3.4 Programmatic Trust

Trust failure amplifies Molochian dynamics. When agents doubt counterpart reliability, preemptive defection becomes rational. Transaction costs rise, group size shrinks, and cooperation collapses.

Smart contracts enable atomic commitments, escrow, and conditional execution without reliance on interpersonal trust [17]. Parties trust the execution environment rather than each other. This reduces coordination costs and enables high-speed formation of temporary organizations.

Research on decentralized autonomous organizations demonstrates that protocol-enforced trust supports fluid collaboration across geographic and institutional boundaries [18].

3.5 The Oracle Problem and Protocol Limitations

Protocols are not panaceas. They excel at enforcing internal consistency (e.g., "Bob cannot spend Alice's coins") but struggle with external truth (e.g., "Did the shipment arrive?"). This "Oracle Problem" relies on trusted hardware or economic bonding to bridge the gap between the ledger and the physical world.

However, the "Protocol Exit" does not require protocols to solving everything. It requires them to separate the rules of coordination from the execution of coordination. By moving the base layer of trust—identity, ownership, and contract fulfillment—into immutable code, we reduce the surface area vulnerable to Molochian decay.

3.6 Separation of Ledger and Market Logic

Daniel Schmachtenberger identifies governance capture as a central driver of the meta-crisis [19]. When the same entity controls both rule-setting and participation, incentive manipulation is inevitable. Protocols separate ownership records from value exchange mechanisms. The ledger defines state; markets operate atop it. This separation mirrors successful architectural patterns in computing [20], ensuring robustness through modularity.

4. Conclusion: The Race to the Top

Modern civilization remains locked in competitive dynamics that reward short-term extraction over long-term value creation. These dynamics persist because they arise from structural incentives rather than individual intent.

Escaping Moloch traps requires re-architecting coordination systems so that cooperative behavior aligns with rational self-interest. Protocols offer such an architecture by embedding cooperation into the fabric of interaction.

The transition from Leviathan to protocol represents a shift from coercive governance to constraint-based governance. Success depends on the careful design of incentive gradients that reward stewardship, contribution, and regeneration.

Binding Moloch requires mathematics, cryptography, and systems design rather than moral appeal. The future of coordination belongs to infrastructures where the winning move expands the commons rather than depleting it.

References

- Alexander, S. (2014). Meditations on Moloch. Slate Star Codex.

- Yudkowsky, E. (2008). Artificial Intelligence as a Positive and Negative Factor in Global Risk. Global Catastrophic Risks.

- Warren, E., & Tyagi, A. W. (2003). The Two-Income Trap. Basic Books.

- Nash, J. (1950). Equilibrium Points in N-Person Games. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Frank, R. H. (2011). The Darwin Economy. Princeton University Press.

- Hobbes, T. (1651). Leviathan.

- Norenzayan, A. (2013). Big Gods. Princeton University Press.

- Epstein, S. (1991). Wage Labor and Guilds in Medieval Europe. University of North Carolina Press.

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the Firm. Journal of Financial Economics.

- Merton, R. K. (1940). Bureaucratic Structure and Personality. Social Forces.

- Tainter, J. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

- Himmelstein, D. U., et al. (2014). Administrative Costs in US Healthcare. BMC Health Services Research.

- Ginsberg, B. (2011). The Fall of the Faculty. Oxford University Press.

- Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.

- Buterin, V. (2014). Ethereum White Paper.

- Axelrod, R. (1984). The Evolution of Cooperation. Basic Books.

- Szabo, N. (1997). Formalizing and Securing Relationships on Public Networks.

- Wright, A., & De Filippi, P. (2015). Decentralized Blockchain Technology and the Rise of Lex Cryptographia.

- Schmachtenberger, D. (2020). The Meta-Crisis. Civilization Research Institute.

- Parnas, D. L. (1972). On the Criteria To Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules. Communications of the ACM.